# we are reading the data directly from the internet

biochem <- read_tsv("http://mtweb.cs.ucl.ac.uk/HSMICE/PHENOTYPES/Biochemistry.txt", show_col_types = FALSE) |>

janitor::clean_names()

# simplify names a bit more

colnames(biochem) <- gsub(pattern = "biochem_", replacement = "", colnames(biochem))

# we are going to simplify this a bit and only keep some columns

keep <- colnames(biochem)[c(1,6,9,14,15,24:28)]

biochem <- biochem[,keep]

# get weights for each individual mouse

# careful: did not come with column names

weight <- read_tsv("http://mtweb.cs.ucl.ac.uk/HSMICE/PHENOTYPES/weight", col_names = F, show_col_types = FALSE)

# add column names

colnames(weight) <- c("subject_name","weight")

# add weight to biochem table and get rid of NAs

# rename gender to sex

b <- inner_join(biochem, weight, by="subject_name") |>

na.omit() |>

rename(sex=gender)Stats Bootcamp - class 13

Hypothesis testing

Prepare mouse biochem data

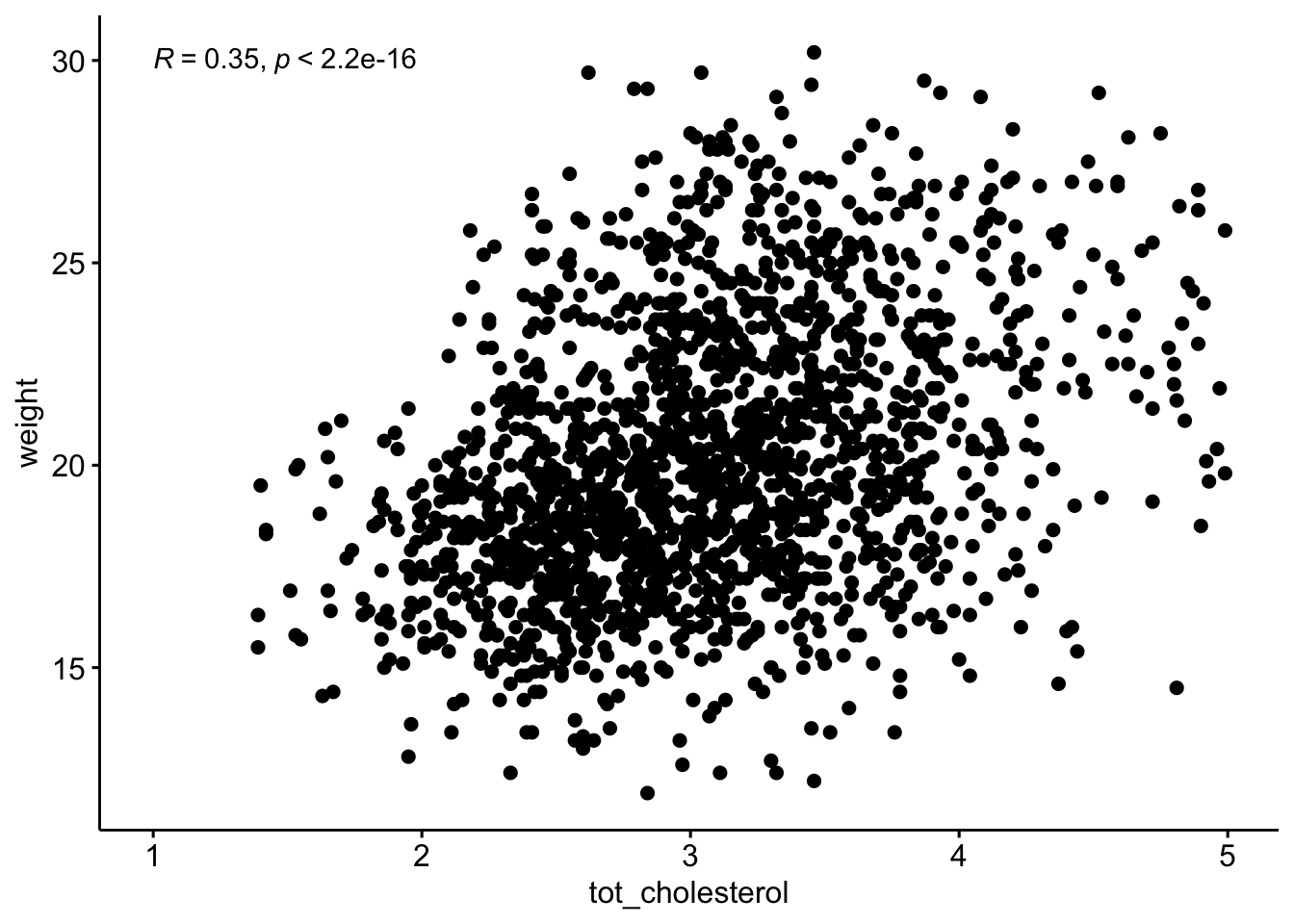

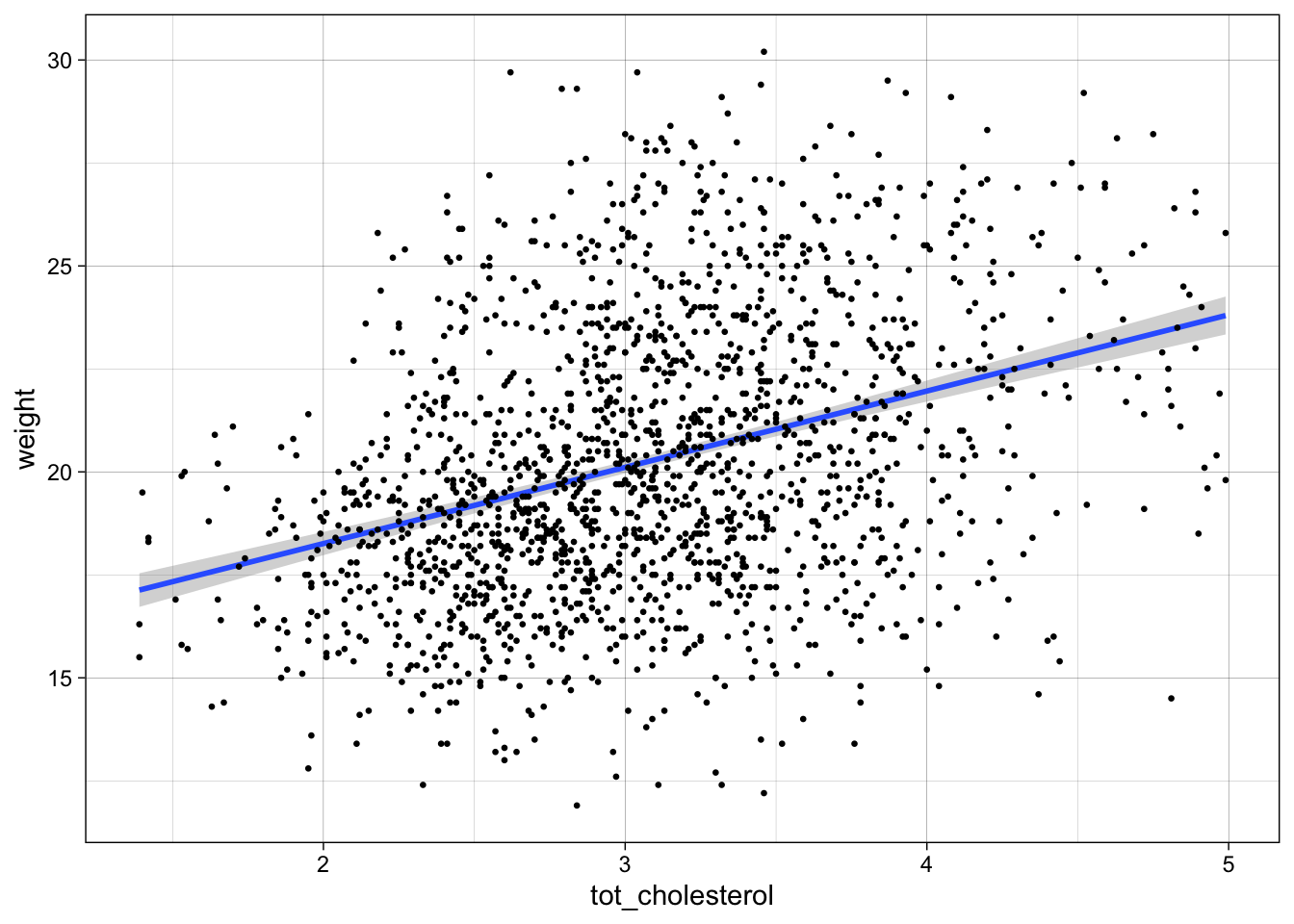

Association between mouse \(weight\) and \(tot\_cholesterol\)

ggscatter()we previously established these are normal enough > \(\mathcal{H}_0\) is no (linear) relationship between \(tot\_cholesterol\) and \(weight\)

b |>

cor_test(??, ??,

method = "??"

)P value well below 0.05

\(\mathcal{H}_0\) is no relationship between \(tot\_cholesterol\) and \(weight\) NOT WELL SUPPORTED

So there is a (linear) relationship between \(tot\_cholesterol\) and \(weight\)

Visualize Pearson correlation

ggscatter(data = b,

y = "weight",

x = "tot_cholesterol"

) +

stat_cor(method = "pearson",

label.x = 1,

label.y = 30)

Manual calculation of Pearson correlation

\(Corr(x,y) = \displaystyle \frac {\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_{i} - \overline{x})(y_{i} - \overline{y})}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sqrt(x_{i} - \overline{x})^2 \sqrt(y_{i} - \overline{y})^2}\)

# mean total cholesterol

m_chol <-

# average weight

m_weight <-

# difference from mean total cholesterol

diff_chol <-

# difference from mean total weight

diff_weight <-

# follow formula above

manual_pearson <-

manual_pearsonSpearman Correlation (nonparametric)

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficientor Spearman’s ρ, named after Charles Spearman is a nonparametric measure of rank correlation (statistical dependence between the rankings of two variables). It assesses how well the relationship between two variables can be described using a monotonic function.

More info here.

b |>

cor_test(weight, tot_cholesterol,

method = "??"

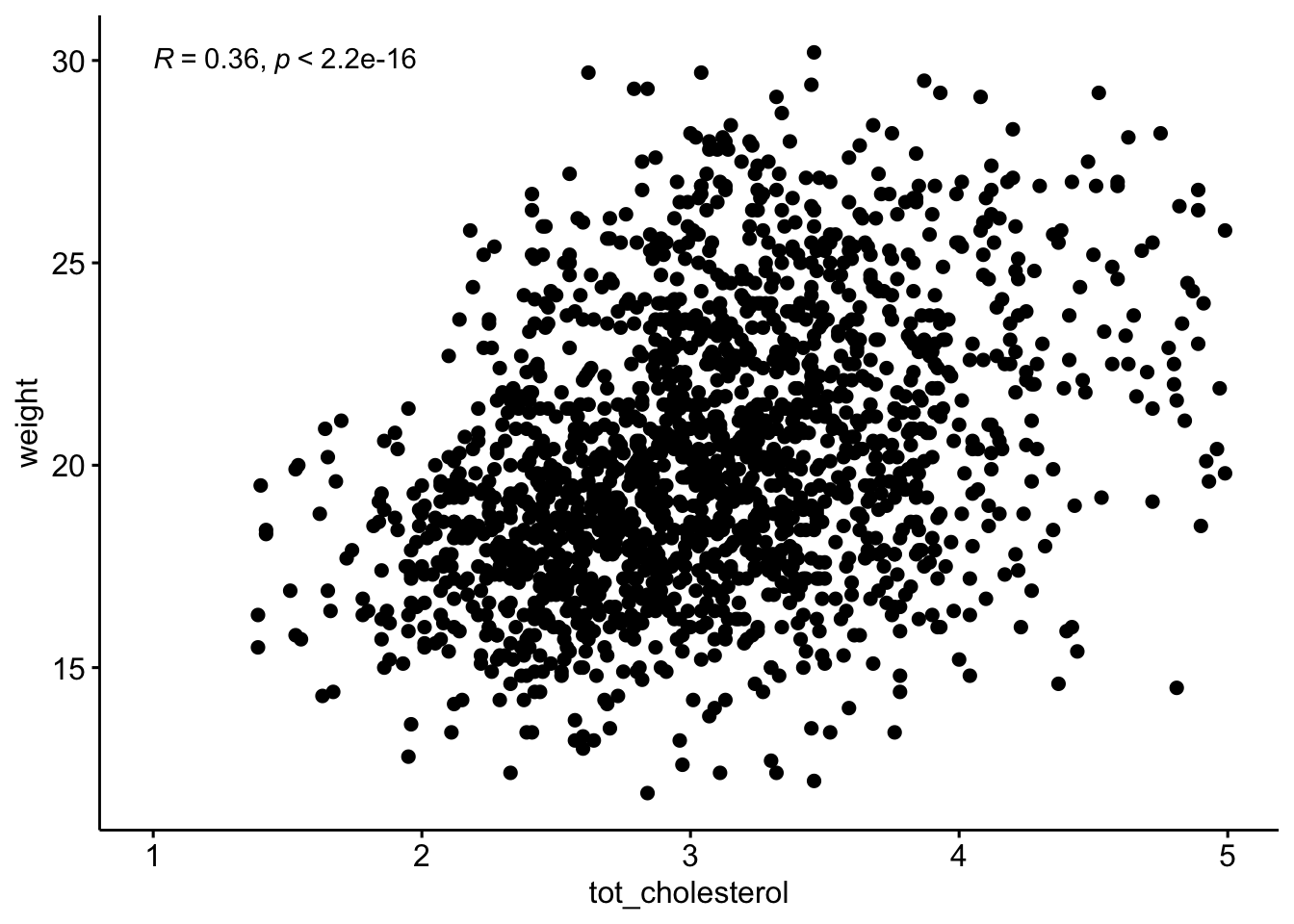

)P value well below 0.05

\(\mathcal{H}_0\) is no relationship between \(tot\_cholesterol\) and \(weight\) NOT WELL SUPPORTED

Visualize Spearman correlation

ggscatter(data = b,

y = "weight",

x = "tot_cholesterol"

) +

stat_cor(method = "spearman",

label.x = 1,

label.y = 30)

Let’s create a hypothetical example

create tibble \(d\) with variables \(x\) and \(y\)

\(x\), 1:50

\(y\), which is \(x^{10}\)

d <- tibble(

x=??,

y=??). . .

scatter plot

ggscatter(data = d,

x = "x",

y = "y")Pearson

d |>

cor_test(x, y,

method = "pearson"

) |>

select(cor). . .

Spearman

d |>

cor_test(x, y,

method = "spearman"

) |>

select(cor)Additional examples with correlation

compare 1 variable to all other quantitative variables

\(weight\)

b |>

cor_test(??) |>

gt()relationship between \(weight\) and \(tot\_cholesterol\) by \(sex\)

b |>

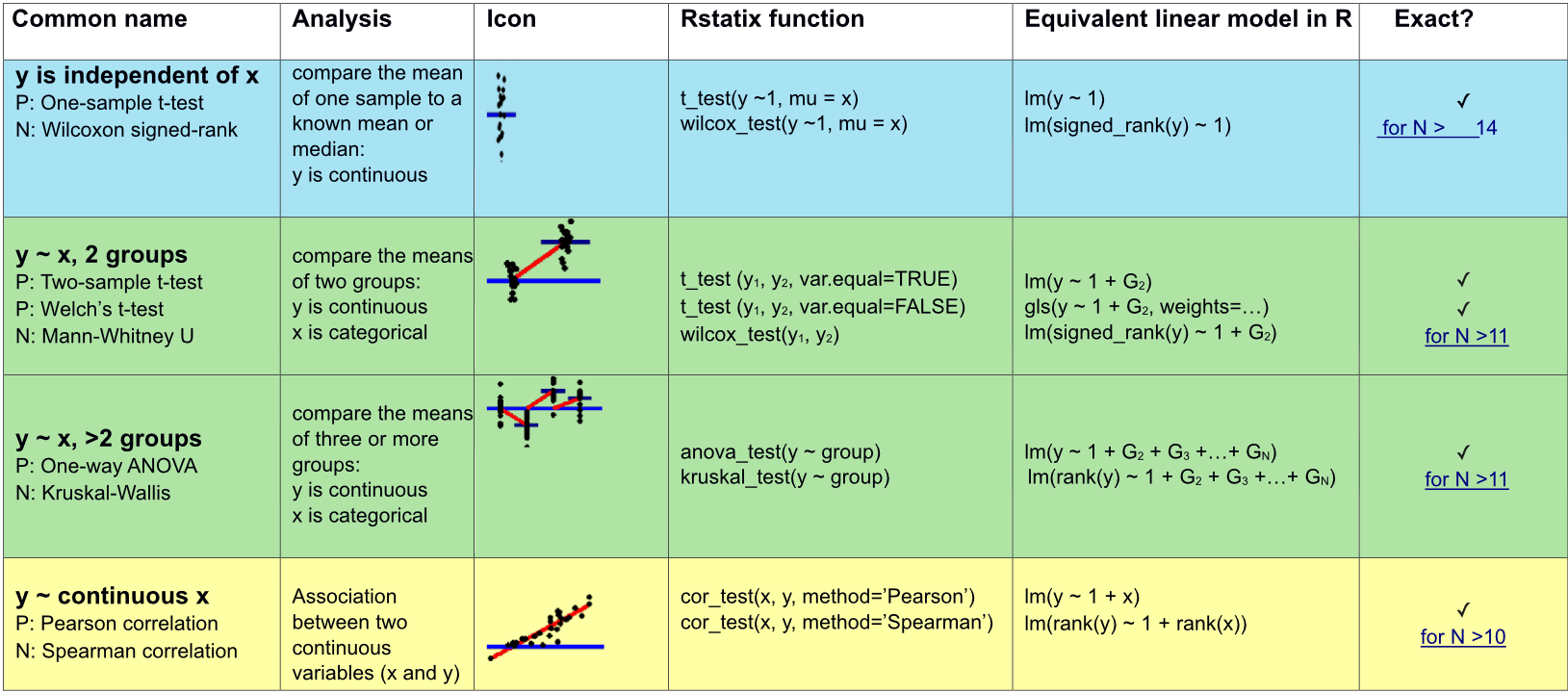

gt()Appropriate statistical test cheatsheet

Regression

We are going to change our frame work to learn about regression. The nice thing is that everything we learn for regression is applicable to all the tests we just learned.

The simplicity underlying common tests

Most of the common statistical models (t-test, correlation, ANOVA; etc.) are special cases of linear models or a very close approximation. This simplicity means that there is less to learn. It all comes down to:

\(y = a \cdot x + b\)

This needless complexity multiplies when students try to rote learn the parametric assumptions underlying each test separately rather than deducing them from the linear model.

Equation for a line

Remember:

\(y = a \cdot x + b\)

OR

\(y = b + a \cdot x\)

\(a\) is the SLOPE (2) \(b\) is the y-intercept (1)

Stats equation for a line

Model:

\(y\) equals the intercept (\(\beta_0\)) pluss a slope (\(\beta_1\)) times \(x\).

\(y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x \qquad \qquad \mathcal{H}_0: \beta_1 = 0\)

… which is the same as \(y = b + a \cdot x\).

The short hand for this in R: y ~ 1 + x

R interprets this as:

y = 1*number + x*othernumber

The task of t-tests, lm, etc., is simply to find the numbers that best predict \(y\).

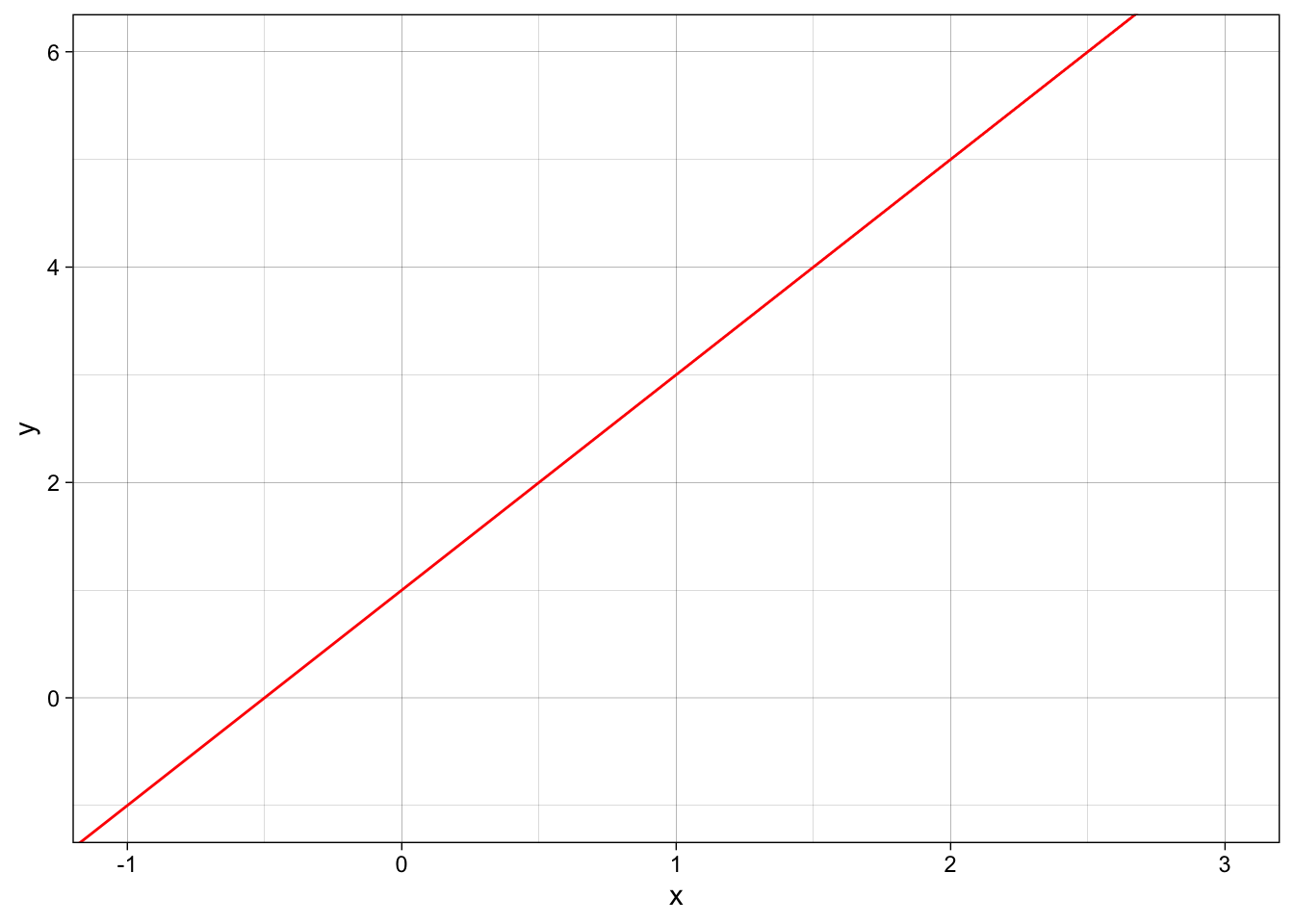

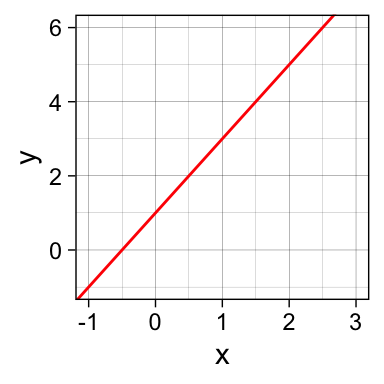

Stats equation for a line

All you need is an intercept (\(\beta_0\)) and a slope (\(\beta_1\)) to get a line:

ggplot(data=d, aes(x=x,y=y)) +

geom_blank() +

geom_abline(intercept = 1,

slope = 2,

col = "red") +

theme_linedraw()

\(\beta_0\) = 1 (the y-intercept), \(\beta_1\) = 2 (the slope)

\(y = \beta_0 \cdot 1 + \beta_1 \cdot x\)

\(y = 1 \cdot 1 + 2 \cdot x\)

\(y = 1 + 2x\)

Our mission: FIND THE BEST \(\beta\) coefficients

Linear Regression

- STEP 1: Make a scatter plot visualize the linear relationship between x and y.

- STEP 2: Perform the regression

- STEP 3: Look at the \(R^2\), \(F\)-value and \(p\)-value

- STEP 4: Visualize fit and errors

- STEP 5: Calculate \(R^2\), \(F\)-value and \(p\)-value ourselves

STEP 1: Can mouse cholesterol levels explain mouse weight?

Plot \(weight\) (y, response variable) and \(tot_cholesterol\) (x, explanatory variable)

ggplot(data = ??,

aes(y = ??,

x = ??)) +

geom_point(size=.5) +

scale_color_manual() +

theme_linedraw()STEP 2: Do the regression

Keep calm and fit a line! Remember: \(y = \beta_0 \cdot 1+ \beta_1 \cdot x\)

linear model equation: \(weight = \beta_0 \cdot 1 + \beta_1 \cdot tot\_cholesterol\)

\(\mathcal{H}_0:\) \(tot\_cholesterol\) does NOT explain \(weight\) Null Hypothesis: \(\mathcal{H}_0: \beta_1 = 0\)

\(weight = \beta_0 \cdot 1 + 0 \cdot tot\_cholesterol\) \(weight = \beta_0 \cdot 1\)

\(\mathcal{H}_1:\) Mouse \(tot\_cholesterol\) does explain \(weight\)

\(weight = \beta_0 \cdot 1 + \beta_1 \cdot tot\_cholesterol\)

The cool thing here is that we can assess and compare our null and alternative hypothesis by learning and examining the model coefficients (namely the slope). Ultimately, we are comparing a complex model (with cholesterol) to a simple model (without cholesterol).

https://statisticsbyjim.com/regression/interpret-constant-y-intercept-regression/

STEP 4: Look at the \(R^2\), \(F\)-value and \(p\)-value

# fitting a line

fit_WvC <- lm(

data = ??,

formula = ??)

# base R summary of fit

summary(fit_WvC)That’s a lot of info, but how would I access it? Time to meet your new best friend:

Tidying output

information about the model fit

??(fit_WvC) |>

gt() |>

fmt_number(columns = r.squared:statistic, decimals = 3)information about the intercept and coefficients

??(fit_WvC)|>

gt() |>

fmt_number(columns =estimate:statistic, decimals = 3)save the intercept and slope into variable to use later

chol_intercept <-

chol_slope <-for every 1 unit increase in cholesterol there is a 1.85 unit increase weight

ggplot(data = b,

aes(y = weight,

x = tot_cholesterol)) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

geom_point(size=.5) +

scale_color_manual() +

theme_linedraw()`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Collecting residuals and other information

add residuals and other information

b_WvC <- ??(fit_WvC, data = b)

b_WvCWhat are Residuals

Residuals, \(e\) — the difference between the observed value of the response variable \(y\) and the explanatory value \(\widehat{y}\) is called the residual. Each data point has one residual. Specifically, it is the distance on the y-axis between the observed \(y_{i}\) and the fit line.

\(e = y_{i} - \widehat{y}\)

Residuals with large absolute values indicate the data point is NOT well explained by the model.

STEP 5: Visualize fit and errors

Visualize the residuals OR the error around the fit

ggplot(data = b_WvC,

aes(x = tot_cholesterol, y = weight)) +

geom_point(size=1, aes(color = .resid)) +

geom_abline(intercept = pull(chol_intercept),

slope = pull(chol_slope),

col = "red") +

scale_color_gradient2(low = "blue",

mid = "black",

high = "yellow") +

geom_segment(aes(xend = tot_cholesterol,

yend = .fitted),

alpha = .1) + # plot line representing residuals

theme_linedraw()Visualize the total error OR the error around the null. So no cholesterol fit, just the mean of y.

avg_weight <- mean(b_WvC$weight)STEP 6: Calculate \(R^2\), \(F\)-value, \(p\)-value ourselves

What is \(R^2\)

\(R^2\) — the coefficient of determination, which is the proportion of the variance in the response variable that is predictable from the explanatory variable(s).

\(R^2 = 1 - \displaystyle \frac {SS_{fit}}{SS_{null}}\)

\(SS_{fit}\) — sum of squared errors around the least-squares fit

\(SS_{fit} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (data - line)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_{i} - (\beta_0 \cdot 1+ \beta_1 \cdot x)^2\)

\(SS_{null}\) — sum of squared errors around the mean of \(y\)

\(SS_{null} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (data - mean)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_{i} - \overline{y})^2\)

Calculate \(R^2\)

\(SS_{fit}\) — sum of squared errors around the least-squares fit

ss_fit <- ??

ss_fit\(SS_{null}\) — sum of squared errors around the mean of \(y\)

ss_null <- ??

ss_null\(R^2 = 1 - \displaystyle \frac {SS_{fit}}{SS_{null}}\)

rsq <- 1- ??

glance(fit_WvC) |> select(r.squared). . .

BTW this is the same \(R\) as from the Pearson correlation, just squared:

b |>

cor_test(weight,tot_cholesterol,

method = "pearson") |>

mutate(r2 = cor^2) |>

pull(r2) |>

round(2)Interpret \(R^2\)

There is a 13 % reduction in the variance when we take mouse \(cholesterol\) into account

OR

\(cholesterol\) explains 13% of variation in mouse \(weight\)

What is the F-statistic

F-statistic — based on the ratio of two variances: the explained variance (due to the model) and the unexplained variance (residuals).

\(F = \displaystyle \frac{SS_{fit}/(p_{fit}-p_{null})} {SS_{null}/(n-p_{fit})}\)

\(p_{fit}\) — number of parameters (coefficients) in the fit line

\(p_{null}\) — number of parameters (coefficients) in the mean line

\(n\) — number of data points

Calculate the F-statistic

\(F = \displaystyle \frac{SS_{null} - SS_{fit}/(p_{fit}-p_{null})} {SS_{fit}/(n-p_{fit})}\)

pfit <- ??

pnull <- ??

n <- ??

f <- ??

f

glance(fit_WvC) |> select(statistic)P-values

You don’t really need to know what the \(F-statistic\) is unless you want to calculate the p-value. In this case we need to generate a null distribution of \(F-statistic\) values to compare to our observed \(F-statistic\).

Therefore, we will randomize the \(tot_cholesterol\) and \(weight\) and then calculate the \(F-statistic\).

We will do this many many times to generate a null distribution of \(F-statistic\)s.

The p-value will be the probability of obtaining an \(F-statistic\) in the null distribution at least as extreme as our observed \(F-statistic\).

Let’s get started

# set up an empty tibble to hold our null distribution

fake_biochem <- tribble()

# we will perform 100 permutations

myPerms <- 100

for (i in 1:myPerms) {

tmp <- bind_cols(

b_WvC[sample(nrow(b_WvC)), "weight"],

b_WvC[sample(nrow(b_WvC)),"tot_cholesterol"],

"perm"=factor(rep(i,nrow(b_WvC)))

)

fake_biochem <- bind_rows(fake_biochem,tmp)

rm(tmp)

}

# let's look at permutations 1 and 2

ggplot(fake_biochem |> filter(perm %in% c(1:2)), aes(x=weight, y=tot_cholesterol, color=perm)) +

geom_point(size=.1) +

theme_minimal()Run 100 linear models!

Now we will calculate and extract linear model results for each permutation individually using nest, mutate, and map functions

fake_biochem_lms <- fake_biochem |>

nest(data = -perm) |>

mutate(

fit = map(data, ~ lm(weight ~ tot_cholesterol, data = .x)),

glanced = map(fit, glance)

) |>

unnest(glanced)Visualize the null

Let’s take a look at the null distribution of F-statistics from the randomized values

ggplot(fake_biochem_lms,

aes(x = statistic)) +

geom_density(color="red") +

theme_minimal()remember that the \(F-statistic\) we observed was 255!

ggplot(fake_biochem_lms, aes(x = statistic)) +

xlim(0,f*1.1) +

geom_density(color="red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = f, color = "blue") +

# scale_x_log10() +

theme_minimal()In our 100 randoized simulations, we never see an F-statistic as extreme as the one we observed in the actual data. Therefore:

P < 0.01 or 1/100

Reminder, our calculate P value was:

How to find the best (least squares) fit?

- Rotate the line of fit

- Find the fit that minimizes the Sum of Squared Residuals or \(SS_{fit}\)

- This is the derivative (slope of tangent at best point = 0) of the function describing the \(SS_{fit}\) and the next rotation is 0.

References

Differences between correlation and regression

also more differences between correlation and regression.

Common statistical tests are linear models from Jonas Lindeløv

Linear Regression Assumptions and Diagnostics in R: Essentials

PRINCIPLES OF STATISTICS from GraphPad/SAS.

Statquest: how to go from F-statistic to p-value

StatQuest: Fitting a line to data, aka least squares, aka linear regression.