The Rmarkdown for this class is on github

Outline

- R language history and ecosystem

- Finding help and reading R documentation

- R fundamentals

- Using the R console

- Variables

- Vectors

- Vector types

- Operators

- Vectorization

What is R

From the R core developers:

R is an integrated suite of software facilities for data manipulation, calculation and graphical display. It includes an effective data handling and storage facility, a suite of operators for calculations on arrays, in particular matrices, a large, coherent, integrated collection of intermediate tools for data analysis, graphical facilities for data analysis and display either on-screen or on hardcopy, and a well-developed, simple and effective programming language which includes conditionals, loops, user-defined recursive functions and input and output facilities.

R, like S, is designed around a true computer language, and it allows users to add additional functionality by defining new functions. Much of the system is itself written in the R dialect of S, which makes it easy for users to follow the algorithmic choices made. For computationally-intensive tasks, C, C++ and Fortran code can be linked and called at run time. Advanced users can write C code to manipulate R objects directly.

Many users think of R as a statistics system. We prefer to think of it as an environment within which statistical techniques are implemented. R can be extended (easily) via packages. There are about eight packages supplied with the R distribution and many more are available through the CRAN family of Internet sites covering a very wide range of modern statistics.

Why is R a popular language?

Figure 1: R facilitates the data analysis process. From https://r4ds.had.co.nz/explore-intro.html.

R is a programming language built by statisticians to facilitate interactive exploratory data analysis.

R comes with (almost) everything you need built in to rapidly conduct data analysis and visualization.

R has a large following, which makes it easy to find help and examples of analyses.

- Rstudio/Posit Community

- Bioconductor Support

- R stackoverflow

R works out of the box on major operating systems.

R has a robust package system of packages from CRAN and bioinformatics focused packages from Bioconductor

Publication quality plots can be produced with ease using functionality in the base R installation or provided by additional packages.

R has a built in documentation system to make it easy to find help and examples of how to use R functionality.

It’s free, open-source, and has been around in it’s first public release since 1993.

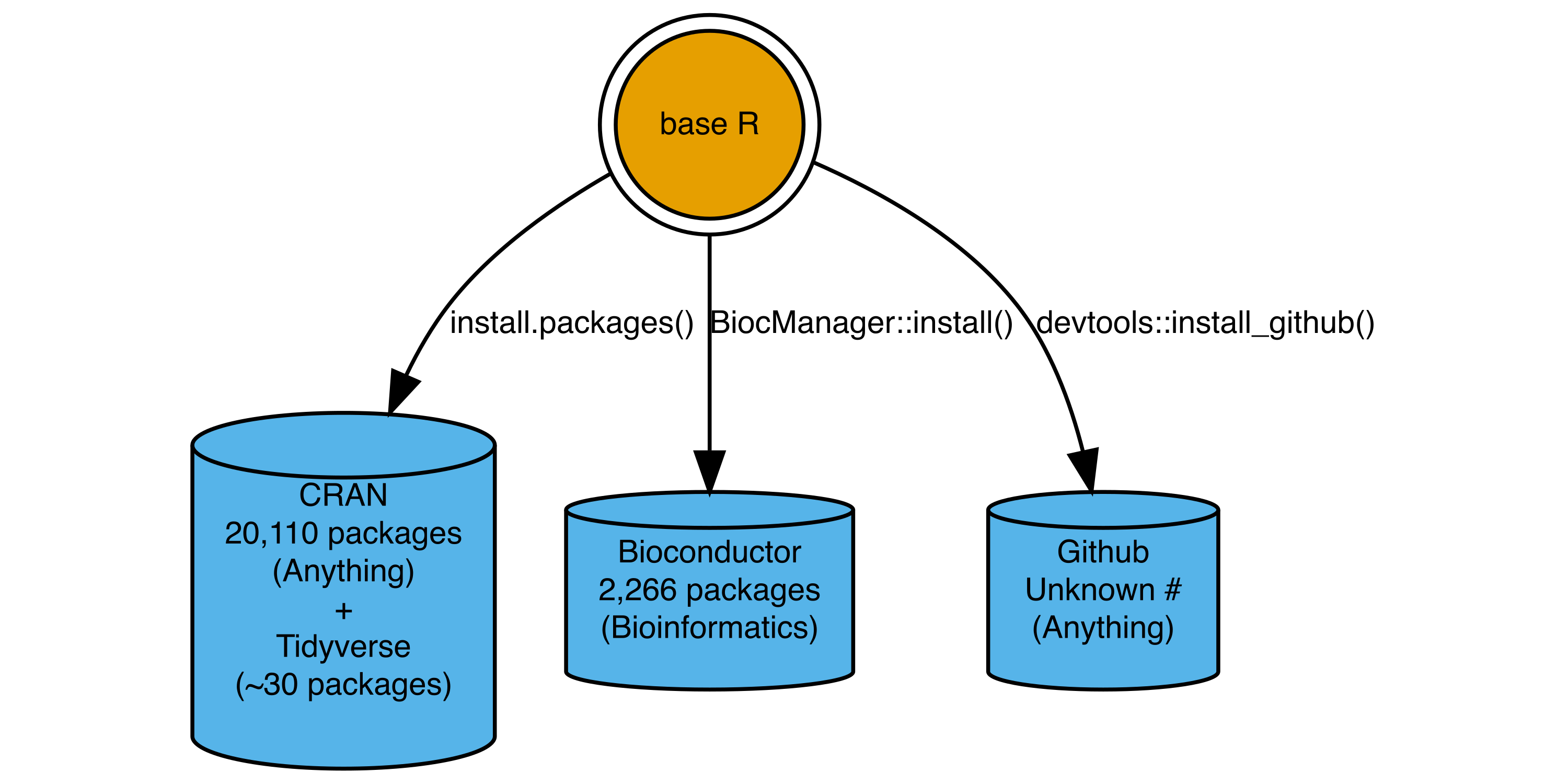

The R ecosystem

When you download R from CRAN, there are a number of packages included in the base installation (e.g. base, stats, and datasets). You can do effective data analysis with only the base installation (e.g. see fasteR tutorial). However a key strength of R is the 10,000+ user-developed packages which extend base R functionality.

Figure 2: Major R package repositories and functions used to install packages.

CRAN is the official R package repository and source for R. The tidyverse (which we will use in subsequent classes) is a set of packages with consistent design principles meant to extend functionality in base R.

Bioconductor hosts and maintains bioinformatics focused packages, built around a set of core data structures and functionality focused on genomics and bioinformatics.

Github hosts software for any software project. It is often used to host R packages in development stages and the actively developed source code for R packages.

Getting help

Built-in documentation

The ? operator can be used to pull up documentation about a function. The ?? operator uses a fuzzy search which can pull up help if you don’t remember the exact function name.

?install.packages??install.packageAlternatively you can click on the help pane and search for help in Rstudio.

Vignettes

Every R package includes a vignette to describe the functionality of the package which can be a great resource to learn about new packages.

These can be accessed via the vignette() function, or via the help menu in Rstudio.

vignette("dplyr")Rstudio Cheatsheets

See Help > Cheatsheets for very helpful graphical references.The base R, dplyr, and ggplot2 cheatsheets are especially useful.

The more you try the more you will learn.

Learning a foreign language requires continual practice speaking and writing the language. To learn you need to try new phrases and expressions. To learn you have to make mistakes. The more you try and experiment the quicker you will learn.

Learning a programming language is very similar. We communicate by organizing a series of steps in the right order to instruct the computer to accomplish a task.

Type and execute commands, rather than copy and pasting, you will learn faster. Fiddle around with the code, see what works and what doesn’t.

Probably everything we do in the class can be done by a LLM such as ChatGPT. These tools can help you, but you will be more effective at using them if you understand the fundamentals. You will also be more productive in the long term if you understand the basics.

Using R interactively with the Console

R commands can be executed in the “Console”, which is an interactive shell that waits for you to run commands.

The > character is a prompt that indicates the beginning of a line. The prompt goes away when a command is being executed, and returns upon completion, or an error.

You can interrupt a command with Esc, Ctrl + c, clicking the STOP sign in the upper right corner, or Session -> Interrupt R or Terminate R.

Before running another command ensure that the > prompt is present.

R can be used as a simple calculator:

1 + 1[1] 23-7 # value of 7 subtracted from 3[1] -43/2 # Division[1] 1.55^2 # 5 raised to the second power[1] 252 + 3 * 5 # R respects the order of math operations.[1] 17Example datasets in R

R and R packages include small datasets to demonstrate how to use a package or functionality. data() will show you many of the datasets included with a base R installation. We will use the state datasets, which contain data on the 50 US states.

state.abb [1] "AL" "AK" "AZ" "AR" "CA" "CO" "CT" "DE" "FL" "GA" "HI" "ID" "IL"

[14] "IN" "IA" "KS" "KY" "LA" "ME" "MD" "MA" "MI" "MN" "MS" "MO" "MT"

[27] "NE" "NV" "NH" "NJ" "NM" "NY" "NC" "ND" "OH" "OK" "OR" "PA" "RI"

[40] "SC" "SD" "TN" "TX" "UT" "VT" "VA" "WA" "WV" "WI" "WY"state.area [1] 51609 589757 113909 53104 158693 104247 5009 2057 58560

[10] 58876 6450 83557 56400 36291 56290 82264 40395 48523

[19] 33215 10577 8257 58216 84068 47716 69686 147138 77227

[28] 110540 9304 7836 121666 49576 52586 70665 41222 69919

[37] 96981 45333 1214 31055 77047 42244 267339 84916 9609

[46] 40815 68192 24181 56154 97914These are R objects, specifically vectors. A vector is collection of values of all the same data type. Note that each position in the vector has a number, called an index. We will talk more about the vectors shortly.

Let’s start using some simple R functions to characterize the size of the US states. Type the following in the console and hit return to execute or call the mean function.

mean(state.area)[1] 72367.98mean is a function. A function takes an input (as an argument) and returns a value.

# simple summary functions

sum(state.area)[1] 3618399min(state.area)[1] 1214max(state.area)[1] 589757median(state.area)[1] 56222length(state.area)[1] 50# sort the values in ascending order

sort(state.area) [1] 1214 2057 5009 6450 7836 8257 9304 9609 10577

[10] 24181 31055 33215 36291 40395 40815 41222 42244 45333

[19] 47716 48523 49576 51609 52586 53104 56154 56290 56400

[28] 58216 58560 58876 68192 69686 69919 70665 77047 77227

[37] 82264 83557 84068 84916 96981 97914 104247 110540 113909

[46] 121666 147138 158693 267339 589757Here each of these functions returned a value, which was printed upon completion with the print() function, and is equivalent to e.g. print(mean(state.area)).

Assigning values to variables

In R you can use either the <- or the = operators to assign objects to variables. The <- is the preferred style. If we don’t assign an operation to a variable, then it will be printed only and disappear from our environment.

x <- length(state.area)

x # x now stores the length of the state.area vector, which is 50[1] 50x <- x + 10 # overwrites x with new value

x + 20 [1] 80Now, what is the value of x?

x = ... ?

...

#[1] 60Vectors and atomic types in R

There are fundamental data types in R which represent integer, `characters, numeric, and logical values, as well as a few other specialized types.

Each of these types are represented in vectors, which are a collection of values of the same type. In R there are no scalar types, for example there is no integer type, rather single integer values are stored in an integer vector with length of 1. This is why you see the [1] next to for example 42 when you print it. The [1] indicates the position in the vector.

42[1] 42Vector types

R has character, integer, double(aka numeric) and logical vector types, as well as more specialized factor, raw, and complex types. We can determine the vector type using the typeof function.

typeof(1.0)[1] "double"typeof("1.0")[1] "character"typeof(1)[1] "double"typeof(1L)[1] "integer"typeof(TRUE)[1] "logical"typeof(FALSE)[1] "logical"typeof("hello world")[1] "character"You can change the type of a vector, provided that there is a method to convert between types.

as.numeric("1.0")[1] 1as.numeric("hello world")[1] NAas.character(1.5)[1] "1.5"as.integer(1.5)[1] 1as.integer(TRUE)[1] 1as.character(state.area) [1] "51609" "589757" "113909" "53104" "158693" "104247" "5009"

[8] "2057" "58560" "58876" "6450" "83557" "56400" "36291"

[15] "56290" "82264" "40395" "48523" "33215" "10577" "8257"

[22] "58216" "84068" "47716" "69686" "147138" "77227" "110540"

[29] "9304" "7836" "121666" "49576" "52586" "70665" "41222"

[36] "69919" "96981" "45333" "1214" "31055" "77047" "42244"

[43] "267339" "84916" "9609" "40815" "68192" "24181" "56154"

[50] "97914" NA, Inf, and NaN values

Often you will find data that contains missing, non-number, or infinite values. There are represented in R as NA, NaN or Inf values.

1 / 0 [1] Inf-( 1 / 0)[1] -Inf0 / 0[1] NaNNA[1] NAAnd these can be detected in a vector using various is.* functions.

is.na()

is.nan()

is.infinite()making vectors from scratch

The c function concatenates values into a vector.

c(2, 5, 4)[1] 2 5 4c(TRUE, FALSE, TRUE)[1] TRUE FALSE TRUEc("dog", "cat", "bird")[1] "dog" "cat" "bird"Vectors can only have 1 type, so if you supply multiple types c will silently coerce the result to a single type.

c(TRUE, 1.9)[1] 1.0 1.9c(FALSE, "TRUE")[1] "FALSE" "TRUE" c(1L, 2.0, TRUE, "Hello")[1] "1" "2" "TRUE" "Hello"Numeric ranges can be generated using : or seq

There are also functions for sampling from various distributions or vectors.

e.g.# get 5 values from a normal distribution with mean of 0 and sd of 1

rnorm(5)[1] 0.46625168 -1.08376829 -0.39536586 -0.08183084 0.33499270# get 5 values from uniform distribution from 0 to 1

runif(5)[1] 0.5951937 0.3089459 0.8601477 0.1417087 0.3356661# sample 5 area values

sample(state.area, 5)[1] 121666 9304 2057 589757 24181Subsetting vectors in R

R uses 1-based indexing to select values from a vector. The first element of a vector is at index 1. The [ operator can be used to extract (or assign) elements in a vector. Integer vectors or logical vectors can be used to extract values.

# extract the second value from the state area and name vectors

state.area[2][1] 589757state.name[2][1] "Alaska"# extract the 1st, 3rd, and 5th name

state.name[c(1, 3, 5)][1] "Alabama" "Arizona" "California"# extract a range of names from 2 -> 7

state.name[2:7][1] "Alaska" "Arizona" "Arkansas" "California"

[5] "Colorado" "Connecticut"Extracting a value that does not (yet) exist will yield an NA

state.name[51][1] NAExercise:

What is the total area occupied by the 10 smallest states? What is the total area occupied by the 10 largest states?

[1] 84494[1] 1808184[1] 1808184Using vectors and subsetting to perform more complex operations

What if we wanted to know which states have an area greater than 100,000 (square miles)?

We can do this in a few steps, which will showcase how simple vector operations, when combined become powerful.

First we can use relational operators to compare values:

# are the values of x equal to 10?

x <- 6:10

x == 10[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUEx > 10 : are the values of x greater than 10

x >= 10: are the values of x greater than or equal to 10

x < 10 : are the values of x less than 10

x <= 10: are the values of x less than or equal 10

These operators fundamentally compare two vectors.

# which values of x are equal to the values in y

y <- c(6, 6, 7, 7, 10)

x == y[1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUEHere, when we ask x < 10 R internally recycles 10 to a vector the same length as x, then evaluates if each element of x is less than 10.

See ?Comparison or ?>`` for help menu on relational operators.

With this we can now ask, are the state.area values greater than 100000?

state.area > 100000 [1] FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[12] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

[23] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

[34] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE

[45] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEThe returned logical vector can be used to subset a vector of the same length. The positions that are TRUE will be retained, whereas the FALSE positions will be dropped.

# return the area values > 100000

state.area[state.area > 100000][1] 589757 113909 158693 104247 147138 110540 121666 267339# alternatively find the position of the TRUE values using which()

which(state.area > 100000)[1] 2 3 5 6 26 28 31 43But how do we find the state names with areas over 100,000?

For this dataset the names of the states are in the same order as the state areas.

Therefore:

state.name[state.area > 100000][1] "Alaska" "Arizona" "California" "Colorado" "Montana"

[6] "Nevada" "New Mexico" "Texas" Exercise:

Let’s answer a related question, how many states are larger than 100,000 square miles?

Using the sum() function works because TRUE is stored as 1 and FALSE is stored as 0.

Replacing or adding values at position

Values in a vector can be also replaced or added by assignment at specific indexes. In this case the bracket [ notation is left of the assignment operator <-. You can read this as assign value on right to positions in the object on the left.

This is a very useful syntax to modify a subset of a vector:

x <- c(1, NA, 2, 3)

# replace all values > 1 with 100

x[x > 1] <- 100

x[1] 1 NA 100 100is.na() returns TRUE if a value is NA, FALSE otherwise:

# replace NA values with -100

x[is.na(x)] <- -100

x[1] 1 -100 100 100R operations are vectorized

As you’ve seen, operations in R tend to execute on all element in a vector. This is called vectorization, and is a key benefit of working in R.

For example, say we wanted to take the natural log of some numbers. For this we use the log function.

x <- 1:5

log(x)[1] 0.0000000 0.6931472 1.0986123 1.3862944 1.6094379If you are used to programming in other languages (e.g C or python) you might have written a for loop to do the same, something like this.

for (i in x) {

log(i)

}In R this is generally not necessary. The built in vectorization saves typing and makes for very compact and efficient code in R. You can write for loops in R (more on this later in the course) however using the built in vectorization is generally a faster and easier to read solution.

Review

To review today’s material, do the following:

For each section with code, try out your own commands. You will learn faster if you type the code yourself and experiment with different commands. If you get errors, try to find help, or ask questions in the class slack channel.

Acknowledgements and additional references

The content of this lecture was inspired by and borrows concepts from the following excellent tutorials:

https://github.com/sjaganna/molb7910-2019 https://github.com/matloff/fasteR https://r4ds.had.co.nz/index.html https://bookdown.org/rdpeng/rprogdatascience/ http://adv-r.had.co.nz/Style.html